I think I'm going to try making the RRR a monthly thing. I get to highlight a number of interesting books, without the undertaking being too large that I end up putting it off indefinitely. I'm saying this entry is for "July" but in truth it also covers the last third or so of June. If I get good at these round-ups and more ambitious I won't lean so heavily on what I've already written on Goodreads, and make it more of a capsule review type thing. The headline still includes "literature" underneath Wednesday Afternoon Picnic, so I hope the expansion into non-Japanese literature reviews will still be welcome to you all.

Again, you can find me on Goodreads here, to follow in real-time (Oh my gosh so exciting!) what I'm reading.

Seventeen and J: Two Novels, Kenzaburo Oe

Translated by Luk Van Haute

2 out of 5 stars

Although Oe often uses these themes in his body of work, the two novels (said designation being extremely generous; they're novellas, really) gathered here are connected by the themes of politics and sexual perversion. And I'm sure at the time, when Oe was young and with not a lot of work to his name, these two pieces were quite extraordinary in a Ooh-look-at-this-literary-wunderkind-so-much-talent-for-his-age kind of way. But now that we know what Oe's work would become with time and practice, the novellas here are quite lackluster, frankly. Oe at his best uses extreme elements with a light touch, grace, nuance, what have you. Nuance is the last thing on display in these novellas.

Seventeen is about a masturbating (seriously, the narrator is constantly talking about and/or doing it), self-loathing teenager who becomes a member of the youth nationalist movement. It's a straw-man argument, basically, associating this totally hateful, pitiful character with conservative politics, and Oe's fiercely leftist tendencies are so obvious and hamfisted he got death threats and harassment from said right party for Seventeen and it's sequel (which, as noted in this book's introduction, Oe refuses to have translated out of legitimate fear from the response he got publishing it in the first place). J is almost two completely separate stories linked by one character, the first about J's wife shooting her art film with a bunch of their mutual friends/sexual conquests, and the next taking place sometime in the future and follows J as he helps induct a young ward in the ways of being a chikan, men who sexually harass women on the train.

Both deal with some heavy, twisted stuff but Oe doesn't know how to handle them really—it feels like he's writing purely for shock value, to illustrate/tie thematically to whatever he wants to complain about in the state of affairs of Japan. Oe is an unbridled idealist in these works, and they exist purely to pummel you into a conceptual submission. Seventeen and J are interesting from a historical perspective, seeing evolution in Oe's writing and the effects these incendiary works would have on the public, and then back to him, but they're not the best literature. Oe is capable of much better.

Mist, Miguel de Unamuno

Translated by Warner Fite

4 out of 5 stars

The original nivolla (you'll understand this term if you read the book). This book was recommended to me by a translator/student friend who workshopped a translation she did of Unamuno. I loved the short story she translated, and she suggested I read this novel for more.

Mist has a whisper-thin plot—man falls in love with a woman who's in love with someone else sort of deal. But plot isn't really quite the point of the novel. It's a thoroughly post-modern/meta-fictional book, though it came out well before either of those terms existed. I don't really want to spoil the surprises in store, but I will be frank, you might find it kind of boring in the beginning (at least I did). The whole thing starts to unravel, so to speak, in the second half, but if you like meta-fictional games in your books, read Mist, one of the earliest. I might have to reread it, in case there are things to catch in the beginning that I couldn't appreciate not knowing the end.

The Art of Fiction, John Gardner

4 out of 5 stars

I'll confess: I have literary aspirations besides those of translating. I wouldn't say I'm any good, but I enjoy it doing it, and getting feedback and seeing how I can improve, and I certainly love the idea of being a novelist... The goal for me now is to start practicing regularly now that I'm not taking classes in the subject. We'll see if I ever get anywhere with it.

So I picked up this of the many guides, because one, John Gardner, and two, my own creative writing teacher mentioned in passing as one of the good ones.

Gardner

is hilariously judgmental in this book, and has almost impossibly high/old-fashioned

standards of literature, but the information and lessons here are undeniably useful

and easy to grasp. I wouldn't agree with everything Gardner says about

the art of writing literary fiction (though who am I to argue against

him) but his thoughts are so well laid out that reading this book would

be helpful for anyone, if only to figure out where s/he stands. At the very least an interesting read if you're into this kind of thing.

After Dark, Haruki Murakami

Translated by Jay Rubin

3 out of 5 stars (maybe 2.5 out of 5)

This is technically a reread, since I read After Dark immediately after it came out the first time.

You know what? After Dark is not that great. I feel like everyone was on a Kafka on the Shore high when After Dark came out in America, because the reviews are generally pretty positive. It's definitely my least favorite Murakami novel now, which is funny because the previous loser, South of the Border, West of the Sun got way better on my second read-through last summer.

Sure, After Dark has got some great atmosphere; it's real nice and tense, and it's got some interesting

characters. The problem is that we don't "know" them like we know characters from

other works, and After Dark is not as clearly "about" something as his other

works. And Murakami explores duality and "this side/other side" themes more

clearly and eloquently, I think, in other works, like Sputnik

Sweetheart. I don't know. On the whole I came away a little disappointed. Not bad, per se, but I feel now like it's a little overrated.

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, Charles Yu

4 out of 5 stars

I fell hard for this book. I wanted to give it 5 stars. Or if Goodreads did half stars, 4.5. It was by far the most fun I've had reading in a long time (I fell hard for Lev Grossman's The Magicians in a similar way).

I suppose it's because I don't read a lot of genre fiction anymore, and while this definitely has a sci-fi bent, it is still very literary. So the sci-fi elements made for a really good novel on a plot-level, but the thematic and emotional resonance made it a story that stuck with me in a way that only good to great literature does.

Plot-wise, a basic synopsis would be that the narrator is a sort of time-travel machine repairman, adrift and lonely, the only child of a time-travel obsessed father and a put-upon mother. Eventually he sees his future self and accidentally/impusively kills him, causing himself to be stuck in a time loop.

The novel reminded me of a number of different things. It reminded me of Murakami in a couple different ways, partially because of Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World's sci-fi bent, but also Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball, 1973's fragmented style and depressed, adrift loner first person narrator. And it also reminded me of A Wild Sheep Chase in that it starts off sort of not about anything but then all of a sudden, much later than you might expect it to, gets very plot-heavy. But it also reminded me of George Saunders, particularly in his novella Pastoralia, in that it deals with a absurd, weird, almost fantastical job that's presented as if it were the most banal thing in the world. A very potent combination, and Yu has some hilarious one liners, and also some of the most emotionally wrenching passages too.

The only drawback is that time travel stories are basically impossible to be fully satisfying. They almost always end in some sort of weird way, whether totally confusing or illogical or by some deux ex machina, which is sort of a necessity, because otherwise, well, the whole infinite loop thing. But this book was SO much fun, that I would recommend this book to just about anybody. I am very much looking forward to reading more of Yu's work.

The Private Lives of Trees, Alejandro Zambra

Translated by Megan McDowell

4 out of 5 stars

This was another book that I was kind of surprised how blown away by how good it was. It's quietly powerful, especially given that it is so short—only 90 odd pages.

It starts off with Julian telling a bedtime story to Daniella, the daughter of his wife Veronica, about trees who basically just sort of chat with other. But the narrative digresses to Julian's romantic past, how he met Veronica, Daniella's potential future life, etc. The narrator states clearly early on that the novel will end when Veronica comes home, but as the novella goes on, it becomes increasingly unclear whether she will come back at all.

I can't help but make another Murakami comparison; in this case, it reminds me of the short story "Honey Pie" from after the quake. The similarities are pretty intriguing, though in all likelihood completely coincidental. They both follow failed/struggling writers (Julian wants to write but seems to have writer's block of some kind; Junpei can only write short stories but not a novel; also I just noticed their names start with J) and both stories start with the telling of a bedtime story about anthropomorphized non-humans (bears in "Honey Pie," trees here) to a girl that is not biologically theirs. They also, at least to some extent, have to deal with the hardships of new, makeshift families. Tonally they are quite different; "Honey Pie" overall is a happy story, with a touch of melancholy, Trees has sort of the opposite proportions. Trees is incredibly moving however, made all the better that it's a story that you can finish in one sitting, while at the same time deeper and more satisfying than just a short story. I highly recommend it, and I super want to read Zambra's Bonsai now too.

And that's what I've read this past July (and some of June). I also started David Foster Wallace's Girl With Curious Hair, though I have many more stories to read, and am halfway through Kevin Brockmeier's latest novel The Illumination. Look forward to reviews of these in roughly a month's time.

Showing posts with label kenzaburo oe. Show all posts

Showing posts with label kenzaburo oe. Show all posts

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Saturday, June 11, 2011

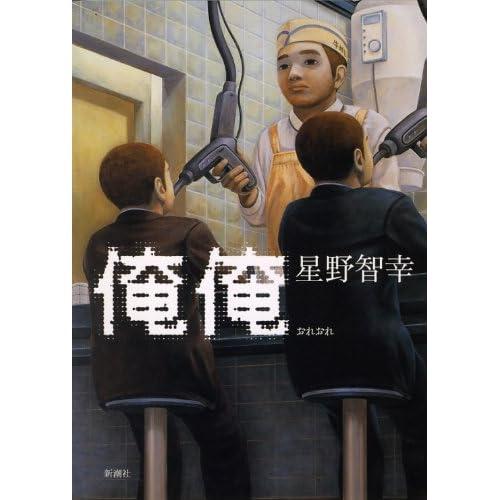

The 2011 Kenzaburo Oe Prize - 俺俺

Anyone with a passing interest in Japanese literature probably knows who Kenzaburo Oe is, if only by virtue of being one of only two Japanese to win the Nobel Prize for Literature back in 1994. That doesn't mean you've read him of course; for instance, I only got around to reading him about two years ago. If you haven't, A Personal Matter is quite good, as is The Changeling. The Silent Cry is another book that is cited among his best, though I haven't read that one yet.

Oe is an intensely personal, intensely intellectual, intensely political writer. He's a big issues kind of writer, even when the plot points seem to echo exactly events in his own life. So it's not surprising that the Academy was drawn to Oe as a candidate for the Nobel Prize, since, coincidentally or not, many of the winners are deeply political writers or individuals. So it's also not surprising that in Japan, he has a literary award in his honor. I mean, how much more internationally renowned can you get as a non-English writing author than winning the Nobel Prize?

I found out about the Kenzaburo Oe Award when I was exploring Gunzo a few months ago, since they made the announcement for the 2011 winner in their May issue. (Gunzo reporting it because both Gunzo and the award are run/sponsored by Kodansha.) It was established in honor of both the 100th anniversary of Kodansha being a company and the 50th "writing anniversary" of Kenzaburo Oe (which by the way, how much more perfect could that timing have been??).

Oe alone chooses the winner—the best novel of the past year.

The Kenzaburo Oe Prize winner is supposed to represent the best of the young generation's "literary intellectuals." It has no cash prize, but the work is to be translated into foreign languages for international publication. In the five years this prize has been acted, I don't think a single work has hit American or British bookshelves. Which I suppose isn't too surprising. I don't know the details about who gets to translates it or when or how, but even if it does get translated, I'm sure very few American publishers want to publish heady, "intellectual" novels from Japan. Just manga, sci-fi/fantasy/light novels, Murakami, and crime fiction please!

Partially inspired by Hopeful in Nagoya's recent diving into of Japanese book reviewing, I decided to try and learn more about this latest winner of the Kenzaburo Oe Prize.

The work is called 俺俺 by 星野智幸, or, Ore Ore by Tomoyuki Hoshino. This title would be hard to translate - it's a repetition of the word "I" or "me," used by dominant, confident, or familiar males, but the title refers to おれおれ詐欺, which is the term for a kind of phone scam. Basically, the perp calls an elderly person and pretends that they are their son or grandson, in order to get them to transfer them money from their bank accounts—basically, they say "Hey, it's me!" and trick their victims into thinking they're family.

Which is the basic premise of this story—a guy, only referred to as 俺, or I, goes to a McDonald's, steals his neighbor's cell phone, and commits a phone scam on this strangers' parents. But it gets stranger. According to the summary on Amazon Japan:

When I took the cell phone of the guy sitting next to me at McDonalds, I ended up committing a phone scam. But then I noticed that I was becoming a different I. The I for my bosses and parents, the I who isn't I, the I who is not I, the we that is I-I [literally: the 俺たち俺俺] So many I's that I don't know what is what anymore. Power off, off. Destroy. Before long, my fellow I's, going this way and that, increasing without end, until… A work that makes the reader ask: What is it, to trust another man, in this age of loneliness and despair?

Weird huh? But vague. So I took a look at the book review from the Asahi newspaper. It begins by repeating the basics of the Amazon summary: "I" goes to a McDonald's, on a whim steals a stranger's cell phone, and tricks the stranger's mother into thinking he was her son, and commits bank transfer fraud. Before he knows it, he starts to became that guy. And gradually, he begins to multiply into other "I"s.

The narrator "I" works at a large electronics store called "Megaton." (Kind of like a Best Buy I assume, perhaps in Akihabara). He seems to feel alienated by his job—even if he took over someone else's duties within the store, his day-to-day affairs wouldn't change. He believes his very existence is "weak", and easily replaceable by someone else. His boss is a mean person "incapable of being understood". The pressure to conform, to not stick out for fear of being made fun of, is overwhelming, and he and his fellow coworkers can barely get by working there. His sense of fitting in at work gets worse and worse, until he organizes a community (perhaps a literal place, like a commune) of "I"s, calling themselves (or the place) "I-Mountain" (俺山):

"At "I Mountain", everyone is I… "I Mountain" is a society without conflict with others. All the hearts of the "I"s are connected" - a transparent community where everyone can be understood. In a place like that, I, as a meaningful existence, is coming to an end. I am becoming no more than a part of a larger self, and the I's always living for each other. That experience is what sustains me."

Suffice it to say that as "I Mountain" starts to get larger, some major problems ensue.

The reviewer starts his/her review simply by calling it a "masterpiece" (傑作). The reviewer says the end took them completely be surprise, and even brought them to tears. The reviewer calls it a "monumental work" of contemporary literature, addressing the problems of identity in modern society.

Although the review seems almost a bit hyperbolic, 「俺俺」 sounds complicated, but awesome. In a strange way, it sort of reminds me of Fight Club, probably due to the weird nameless commune aspects, but it sounds like a fascinating work, one whose message would resonate beyond just Japan but throughout the world. When I have some extra cash I might try to pick it up sometime (it can be ordered from the Kinokuniya website if you live in the US). It's also probably worth checking out the other winners of the Kenzaburo Oe Prize, which you can find a list of, in English, on the Prize's Wikipedia page.

Oe is an intensely personal, intensely intellectual, intensely political writer. He's a big issues kind of writer, even when the plot points seem to echo exactly events in his own life. So it's not surprising that the Academy was drawn to Oe as a candidate for the Nobel Prize, since, coincidentally or not, many of the winners are deeply political writers or individuals. So it's also not surprising that in Japan, he has a literary award in his honor. I mean, how much more internationally renowned can you get as a non-English writing author than winning the Nobel Prize?

I found out about the Kenzaburo Oe Award when I was exploring Gunzo a few months ago, since they made the announcement for the 2011 winner in their May issue. (Gunzo reporting it because both Gunzo and the award are run/sponsored by Kodansha.) It was established in honor of both the 100th anniversary of Kodansha being a company and the 50th "writing anniversary" of Kenzaburo Oe (which by the way, how much more perfect could that timing have been??).

Oe alone chooses the winner—the best novel of the past year.

The Kenzaburo Oe Prize winner is supposed to represent the best of the young generation's "literary intellectuals." It has no cash prize, but the work is to be translated into foreign languages for international publication. In the five years this prize has been acted, I don't think a single work has hit American or British bookshelves. Which I suppose isn't too surprising. I don't know the details about who gets to translates it or when or how, but even if it does get translated, I'm sure very few American publishers want to publish heady, "intellectual" novels from Japan. Just manga, sci-fi/fantasy/light novels, Murakami, and crime fiction please!

Partially inspired by Hopeful in Nagoya's recent diving into of Japanese book reviewing, I decided to try and learn more about this latest winner of the Kenzaburo Oe Prize.

The work is called 俺俺 by 星野智幸, or, Ore Ore by Tomoyuki Hoshino. This title would be hard to translate - it's a repetition of the word "I" or "me," used by dominant, confident, or familiar males, but the title refers to おれおれ詐欺, which is the term for a kind of phone scam. Basically, the perp calls an elderly person and pretends that they are their son or grandson, in order to get them to transfer them money from their bank accounts—basically, they say "Hey, it's me!" and trick their victims into thinking they're family.

Which is the basic premise of this story—a guy, only referred to as 俺, or I, goes to a McDonald's, steals his neighbor's cell phone, and commits a phone scam on this strangers' parents. But it gets stranger. According to the summary on Amazon Japan:

When I took the cell phone of the guy sitting next to me at McDonalds, I ended up committing a phone scam. But then I noticed that I was becoming a different I. The I for my bosses and parents, the I who isn't I, the I who is not I, the we that is I-I [literally: the 俺たち俺俺] So many I's that I don't know what is what anymore. Power off, off. Destroy. Before long, my fellow I's, going this way and that, increasing without end, until… A work that makes the reader ask: What is it, to trust another man, in this age of loneliness and despair?

Weird huh? But vague. So I took a look at the book review from the Asahi newspaper. It begins by repeating the basics of the Amazon summary: "I" goes to a McDonald's, on a whim steals a stranger's cell phone, and tricks the stranger's mother into thinking he was her son, and commits bank transfer fraud. Before he knows it, he starts to became that guy. And gradually, he begins to multiply into other "I"s.

The narrator "I" works at a large electronics store called "Megaton." (Kind of like a Best Buy I assume, perhaps in Akihabara). He seems to feel alienated by his job—even if he took over someone else's duties within the store, his day-to-day affairs wouldn't change. He believes his very existence is "weak", and easily replaceable by someone else. His boss is a mean person "incapable of being understood". The pressure to conform, to not stick out for fear of being made fun of, is overwhelming, and he and his fellow coworkers can barely get by working there. His sense of fitting in at work gets worse and worse, until he organizes a community (perhaps a literal place, like a commune) of "I"s, calling themselves (or the place) "I-Mountain" (俺山):

"At "I Mountain", everyone is I… "I Mountain" is a society without conflict with others. All the hearts of the "I"s are connected" - a transparent community where everyone can be understood. In a place like that, I, as a meaningful existence, is coming to an end. I am becoming no more than a part of a larger self, and the I's always living for each other. That experience is what sustains me."

Suffice it to say that as "I Mountain" starts to get larger, some major problems ensue.

The reviewer starts his/her review simply by calling it a "masterpiece" (傑作). The reviewer says the end took them completely be surprise, and even brought them to tears. The reviewer calls it a "monumental work" of contemporary literature, addressing the problems of identity in modern society.

Although the review seems almost a bit hyperbolic, 「俺俺」 sounds complicated, but awesome. In a strange way, it sort of reminds me of Fight Club, probably due to the weird nameless commune aspects, but it sounds like a fascinating work, one whose message would resonate beyond just Japan but throughout the world. When I have some extra cash I might try to pick it up sometime (it can be ordered from the Kinokuniya website if you live in the US). It's also probably worth checking out the other winners of the Kenzaburo Oe Prize, which you can find a list of, in English, on the Prize's Wikipedia page.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)